Physics-based Machine Learning Scheme for Accelerating Simulation of 2D Lower-Hybrid Wave on TST-2 Spherical Tokamak

Po-Han Hou, Naoto Tsujii, Adriana Paluszny

Abstract

Numerical simulation is indispensable for optimizing input parameters and minimizing startup costs in fusion devices. The study proposes a hybrid machine learning approach to model plasma wave propagation, using a Convolutional Neural Network as a baseline, alongside UNet and Fourier Neural Operator (FNO) models, with a Geometry-aware FNO as an extension for arbitrary geometries. The plasma wave equation serves as the governing equation, embedded within a Physics-Informed Neural Operator framework. Data are generated using the partial differential equations derived from the electrostatic dispersion relation with the Spectral-FDM hybrid method. The experimental setup simulates radio frequency heating scenarios in the TST-2 spherical tokamak at the University of Tokyo for modeling lower hybrid waves. The proposed simulation scheme demonstrates a 281.8x acceleration in inference time in the rectangular domain on the FNO model and a 25.8x acceleration in the TST-2 circular geometry while maintaining reliability, with a memory footprint of 498 MB on the Geometry-aware FNO model. This offers the potential for real-time monitoring of the wave structure within the modern edge computing device and facilitates efficient selection of launching parameters for fusion start-up.

Introduction

Fusion energy represents a compelling solution for achieving clean and sustainable power, requiring plasma temperatures around $10^8$ K to overcome the Coulomb barrier that exists between atomic nuclei. There are several approaches of heating techniques inside the tokamak, such as Ohmic Heating, Neutral Beam Injection, Magnetic Induction Heating, and, in this case, Radio Frequency heating, have been devised for application in the TST-2 spherical tokamak to attain these specific conditions. Accurate numerical simulations are essential for predicting plasma behavior and electric field distributions, reducing the need for costly experimental trials.

For plasma wave modeling, traditional numerical methods such as Finite Element Methods (FEM) and the Spectral code are widely acknowledged. The major advantage for Spectral Methods is transforming the wave equations into multiplicative operations in Fourier space but struggling with arbitrary geometries due to their reliance on global basis functions, making it inefficient for non-rectangular geometry. FEM, however, offers flexibility in the meshing of irregular domains but faces challenges in establishing stable solvers for non-local plasma response. With advances in high-performance computing, these methods have become more computationally feasible in a limited time. Recently, deep learning models, particularly Physics-Informed Neural Networks (PINNs), have emerged as surrogate solvers for conventional large-scale solver, accelerating simulations like Reynolds-Averaged Navier-Stokes and Direct Numerical Simulation by orders of magnitude $10^5$ while maintaining reliability via integrating partial differential equations (PDEs) into the learning process to enhance generalizability and robustness.

The study develops and evaluates four deep learning models: ConvNet, UNet, Fourier Neural Operator (FNO), and Geometry-aware FNO (Geo-FNO), which uses the plasma wave equation as the governing model, with a ConvNet as the baseline. The models are exercised in a rectangular domain, with the expansion to the TST-2 geometry, in order to capture the underlying electric field structures launched by radio frequency waves. These field structures are pivotal in accelerating fast electrons and facilitating non-inductive current in tokamak plasmas, both of which are essential for effective heating and sustained operation in the fusion device.

Problem Statement

The study utilizes a hybrid ML technique which integrates physically informed constraints with a network architecture for plasma wave modeling. The plasma wave equation, derived from Maxwell’s equations in a cold plasma medium, serves as the governing equation:

\[\nabla \times \nabla \times \mathbf{E} - \frac{\omega^2}{c^2} \mathbf{K} \mathbf{E} = 0\]where $\mathbf{E}$ is the electric field, $\omega$ is the wave frequency, $c$ is the speed of light, and $\mathbf{K}$ is the cold plasma dielectric tensor.

The widely acknowledged full-wave solver for fusion devices is the All Order Spectral Algorithm (AORSA). However, its computational cost is prohibitively high that generating a single output with a specific parameter set and adaptive high-resolution meshing required approximately 1792 CPU hours. Given the limited timeframe of this study, the simulations were instead conducted under the electrostatic approximation for the lower-hybrid wave. This allowed for validation of the proposed approaches on homogeneous grids with significantly reduced computational overhead.

Electrostatic Approximation and Dispersion Relation

Under the electrostatic approximation, the electric field is expressed by the scalar potential as:

\[\mathbf{E} = -\nabla \Phi\]Assuming no free charge ($\nabla \cdot \mathbf{D} = \rho_f = 0$) and using $\mathbf{D} = \mathbf{K} \mathbf{E}$, the cold plasma dielectric tensor $\mathbf{K}$ is:

\[\mathbf{K} = \begin{bmatrix} S & iD & 0 \\ -iD & S & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & P \end{bmatrix}\]where $S, D, P$ in $\mathbf{K}$ are Stix parameters and $\mathbf{D}$ is the electric displacement field.

The electrostatic dispersion relation can be computed as:

\[S (k_x^2+k_y^2) + P k_z^2 = 0\]The Stix parameters are:

\[\begin{align} S &= 1 - \sum_s \frac{\omega_{ps}^2}{\omega^2 - \omega_{cs}^2}, \\ D &= \sum_s \frac{\omega_{cs}}{\omega} \cdot \frac{\omega_{ps}^2}{\omega^2 - \omega_{cs}^2}, \\ P &= 1 - \sum_s \frac{\omega_{ps}^2}{\omega^2} \end{align}\]where $\omega_{ps}$ and $\omega_{cs}$ are the plasma and cyclotron frequencies for species $s$, respectively.

To account for the electron Landau damping effect along the magnetic field, the $P$ component is modified:

\[\tilde{P} = 1 - \sum_s \frac{\omega_{ps}^2}{\omega^2} \zeta^2 Z'(\zeta)\]where $\zeta = \frac{\omega}{k_\parallel v_{th,e}}$, $Z’(\zeta) = -2 \left(1 + \zeta Z(\zeta)\right)$, and the plasma dispersion function is:

\[Z(\zeta) = \frac{1}{\sqrt{\pi}} \int_{-\infty}^{\infty} \frac{e^{-z^2}}{z - \zeta} \, dz, \quad \text{Im}(\zeta) > 0\]Here, $v_{th,e}$ is the electron thermal velocity, and $k_\parallel$ is the wavevector component parallel to the magnetic field.

Simulation Setup

The numerical solver employed in the research is a hybrid approach that combines the spectral and finite difference method. The parameters setup is based on the LH wave heating configuration of the TST-2 tokamak, with detailed value listed in Table 1.

Table 1: Target plasma parameters for TST-2

| Parameter | Value | Unit |

|---|---|---|

| Target plasma density | $5 \times 10^{16}$ – $1 \times 10^{18}$ | m$^{-3}$ |

| Plasma temperature | 5 – 100 | eV |

| Toroidal magnetic field | 0.1 – 0.2 | T |

| Plasma current | $< 30$ | kA |

| Major radius | 0.36 | m |

| Minor radius | 0.23 | m |

| LH wave frequency | 200 | MHz |

| Toroidal mode number | 10 – 30 | – |

Rectangular Domain

The computational domain is defined on a 2D rectangular grid on the $ZX$-plane ($Z \in [-3, 3]$, $X \in [0, 0.46]$) with a $288 \times 288$ homogeneous grid. The $Z$-axis is horizontal, the $X$-axis is vertical, and the $Y$-axis (into the page) is neglected. The background magnetic field ($B_0$) is homogeneous and oriented along the $z$-axis. Plasma characteristics, including density ($n$) and temperature ($T$), are assumed to be flux functions. Periodic boundary conditions are implemented along $Z$ at $Z = \pm 3$ to mimic the circular geometry of the TST-2, with a boundary electric field launched at $x = 0$.

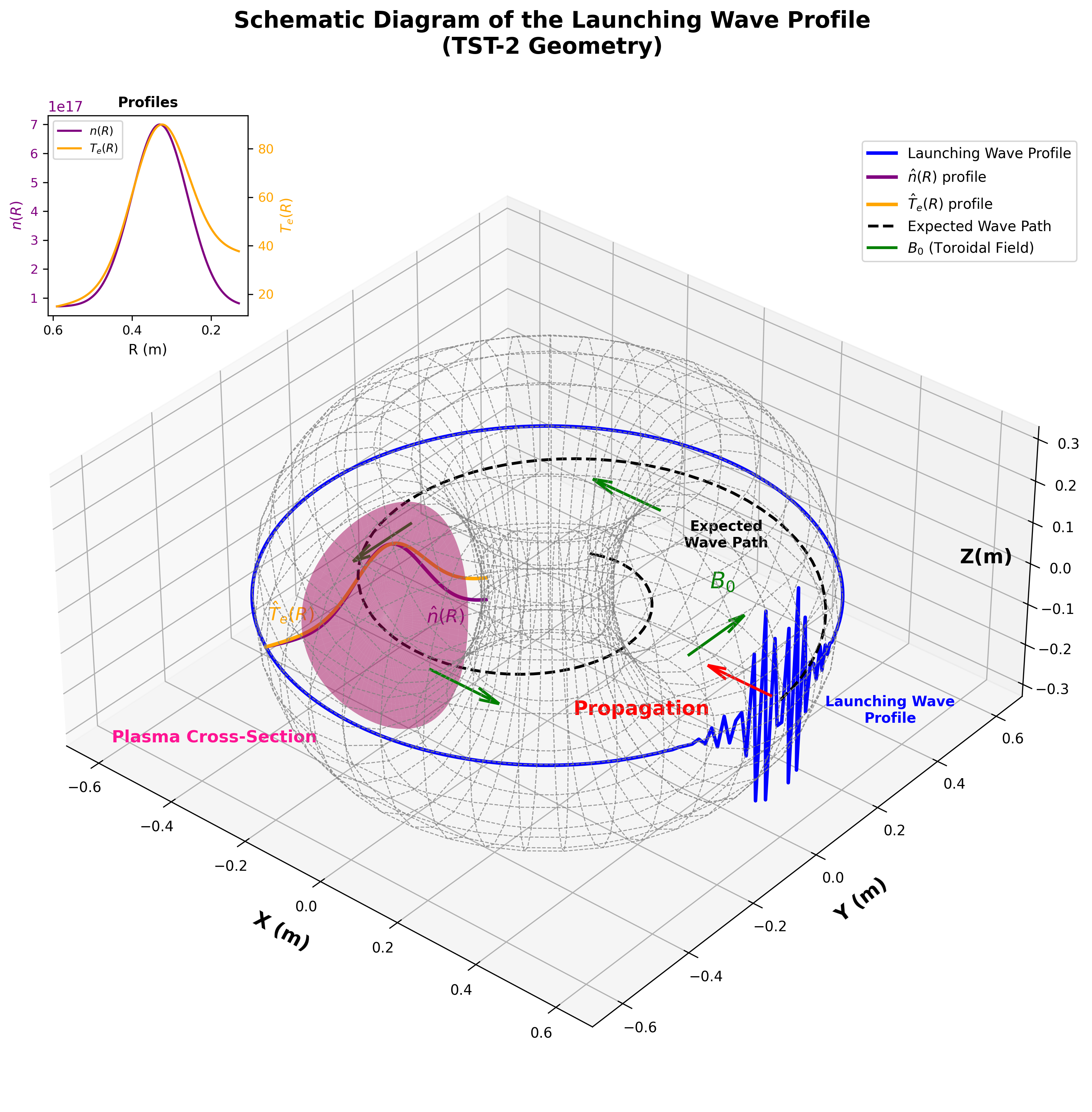

TST-2 Geometry

A 2D top-down projection in the $XY$-plane is used to represent the TST-2 domain geometry with a $512 \times 512$ homogeneous grid. The simulation is done in cylindrical coordinates for the inner wall at R = 0.13 (m) and outer wall at R = 0.59 (m) with azimuth angle ($\phi$). The wave is launched from the outer boundary and propagates into the plasma medium.

Methodologies

The experiment was mainly implemented in Python-PyTorch. For the ML module, a simple ConvNet was used as a baseline, while UNet, FNO, and Geo-FNO are developed as core models. The loss function combines MSE point-wise error analysis, spectral loss, boundary loss, and the physics-informed term based on the plasma wave equation.

Fourier Neural Operator (FNO)

FNO learns to approximate PDE solution operators by performing global convolutions in Fourier space. It utilizes a Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) for the model input, alters spectral coefficients with learned weights, and performs an inverse FFT to return the output. Unlike conventional networks that operate in finite-dimensional Euclidean space, FNO learns mappings in infinite-dimensional function spaces, making it particularly effective for modeling complex physical fields on regular grids.

Geometry-aware FNO (Geo-FNO)

Although FNO statistically achieves good accuracy and accelerates inference compared to conventional solvers, the FFT operation restricts it to a rectangular domain with a homogeneous grid. Geo-FNO improves FNO by learning how to change the coordinates from the physical shape to a regular space, allowing FFT-based operations to still be used. This approach enables efficient modeling of point clouds and non-uniform meshes by approximating the solution operator in Fourier space using a data-driven method.

Loss function and Physics-Informed Operation

To train the artificial neural network, the total loss function \(\mathcal{L}_{\text{total}}\) consists of four components: MSE loss \(\mathcal{L}_{\text{mse}}\), spectral loss \(\mathcal{L}_{\text{spectral}}\), boundary condition loss \(\mathcal{L}_{\text{boundary}}\), and the residual physics-informed loss \(\mathcal{L}_{\text{physics}}\):

\[\mathcal{L}_{\text{total}} = \lambda_{\text{mse}}\mathcal{L}_{\text{mse}} + \lambda_{\text{spectral}}\mathcal{L}_{\text{spectral}} + \lambda_{\text{boundary}}\mathcal{L}_{\text{boundary}} + \lambda_{\text{physics} }\mathcal{L}_{\text{physics}}\]The physics residual loss enforces the governing electrostatic wave equation derived from the dispersion relation. Incorporating the physics-based loss function into model training loss is equivalent to embedding physical laws into the neural networks, which can be therefore considered as physics-informed neural networks.

Results & Discussion

The experiment is conducted in four parts with varying loss weights as shown in Table 2.

Table 2: Loss function weights for each part of the experiment

| Task | $\mathcal{\lambda}_{\text{mse}}$ | $\mathcal{\lambda}_{\text{spectral}}$ | $\mathcal{\lambda}_{\text{boundary}}$ | $\mathcal{\lambda}_{\text{physics}}$ |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part 1 | 1 | 0.01 | 0.1 | 0.01 |

| Part 2 | 1 | 0.01 | 0.1 | 0 |

| Part 3 | 1 | 0.01 | 0.1 | 0.01 |

| Part 4 | 1 | 0.01 | 0.1 | 1 |

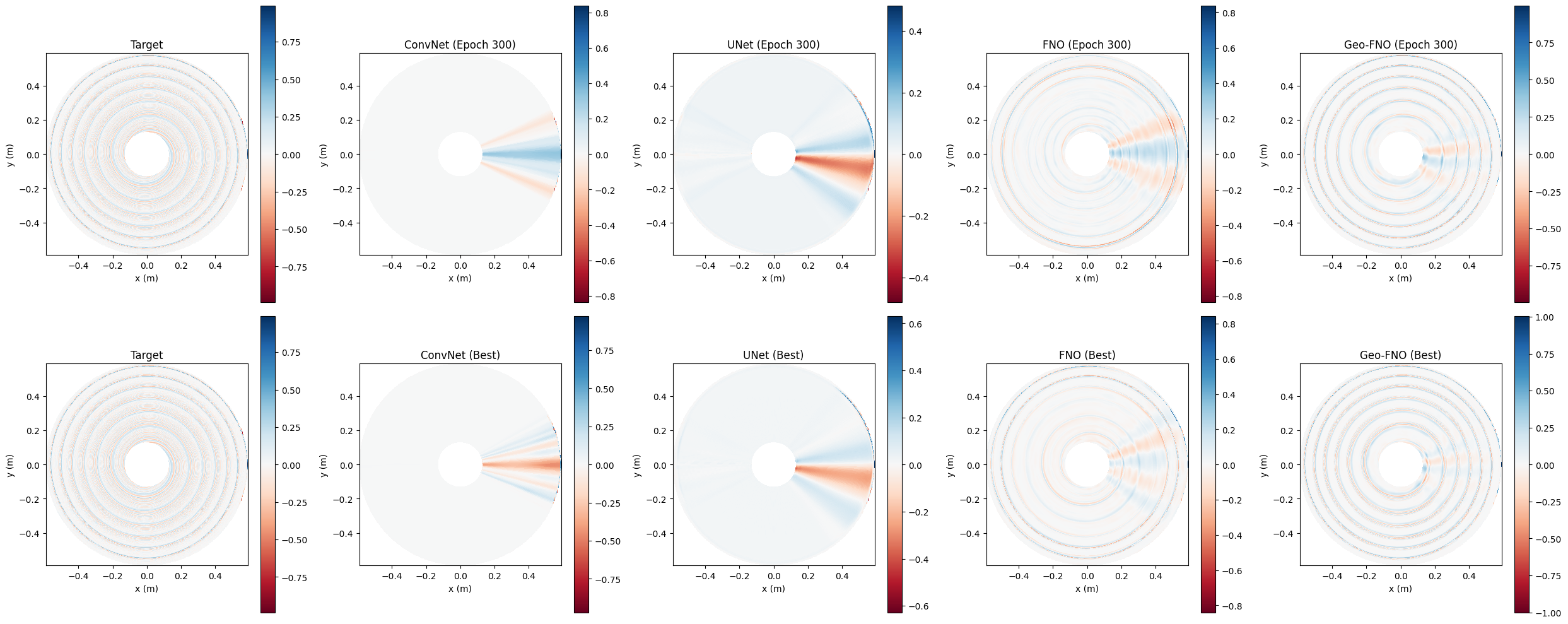

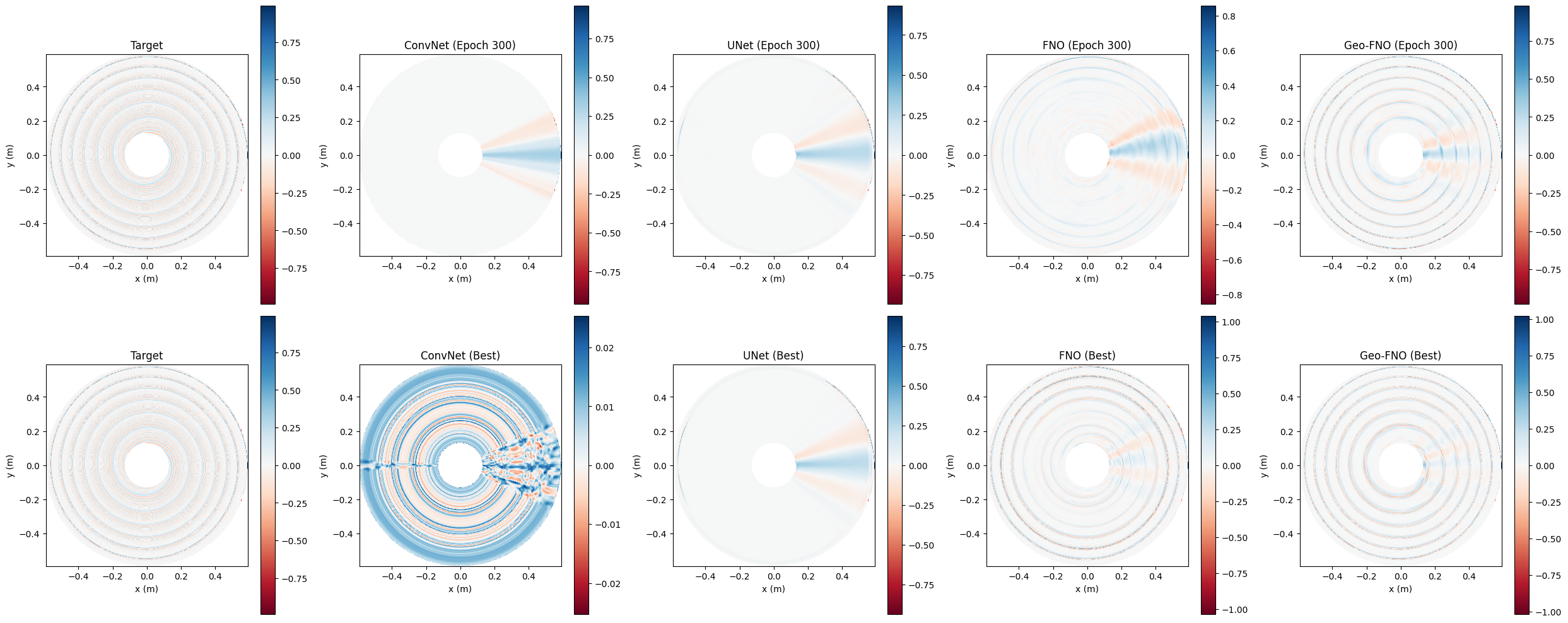

Rectangular domain

The FNO model exhibited strong performance in the rectangular domain. It achieved an average inference time of approximately 3.02 ms, corresponding to a 281.8x speed-up compared to the numerical solver (851 ms), while maintaining comparable accuracy.

TST-2 circular geometry

In this stage, the model is trained in a purely data-driven approach. The inference result shows that the projection capabilities of ConvNet and UNet are insignificant, whereas the model of Geo-FNO shows a tolerable prospect.

When incorporating physics loss (Part 3), Geo-FNO yields reasonably satisfactory results (NMSE: 0.8409, MAE: 0.0769, SSIM: 0.5070).

Overall Evaluation

The study demonstrates that introducing too large a weight to the physics-informed loss term may not necessarily be an ideal solution. FNO achieves notably faster inference compared to UNet due to the $\mathcal{O}(N\log N)$ complexity of FFT-based spectral convolutions. Additionally, Geo-FNO introduces a simple multi-layer perceptron (MLP) to generalize arbitrary geometry into a 2D rectangular domain in the latent space, making the spectral convolution more effectively trainable.

Table 3: Benchmark table for different sets of loss weights

| Model | Part 2 (NMSE) | Part 2 (MAE) | Part 2 (SSIM) | Part 3 (NMSE) | Part 3 (MAE) | Part 3 (SSIM) | Part 4 (NMSE) | Part 4 (MAE) | Part 4 (SSIM) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ConvNet | 2.6869 | 0.0925 | 0.3998 | 1.1470 | 0.0852 | 0.2198 | 1.0042 | 0.0843 | 0.3989 |

| UNet | 1.0384 | 0.0915 | 0.4109 | 1.0134 | 0.0906 | 0.4229 | 1.0251 | 0.0845 | 0.0362 |

| FNO | 1.1336 | 0.0867 | 0.4308 | 1.0300 | 0.0827 | 0.4513 | 1.0017 | 0.0843 | 0.3201 |

| Geo-FNO | 0.7272 | 0.0699 | 0.5533 | 0.8409 | 0.0769 | 0.5070 | 1.8374 | 0.0867 | 0.4335 |

Table 4: Benchmark table for inference time, memory footprint and number of parameters

| Model | Average Inference Time (ms) | Memory Footprint (MB) | Params |

|---|---|---|---|

| Spectral-FDM solver | $482 \pm 17$ | 20.2 (CPU) | - |

| ConvNet (baseline) | $3.26 \pm 0.02$ (147.8x) | 158.39 | 93,922 |

| UNet | $7.25 \pm 0.11$ (66.5x) | 141.00 | 483,042 |

| FNO | $3.68 \pm 0.04$ (130.9x) | 294.00 | 465,546 |

| Geo-FNO | $18.68 \pm 0.03$ (25.8x) | 498.00 | 481,626 |

Conclusion

The study demonstrates the feasibility of a physics-based machine learning scheme for accelerating the simulation of lower hybrid wave propagation in fusion plasmas. By integrating the electrostatic dispersion relation with Landau damping into neural network & operator learning architectures, the proposed prospective model, especially the neural operator, achieves substantial speed increases over 281.8x acceleration in the rectangular domain with FNO and a 25.8x acceleration in the TST-2 geometry with Geo-FNO. This effectively bridges the gap between purely data-driven surrogates and physics-constrained solvers, enabling near real-time inference of wave structures under varying plasma conditions. These capabilities open the door to rapid parameter scanning, real-time monitoring, and more efficient experimental planning in tokamak operations, potentially reducing operational costs and enhancing non-inductive start-up performance for the future comprehensive experiment.

Building on these features, the next phase will extend the framework to fully electromagnetic models using the AORSA full-wave solver, incorporating realistic three-dimensional equilibrium fields. This will allow the surrogate to model characteristic events such as cutoff, mode conversion, wave–particle interactions, and other phenomena beyond the electrostatic approximation. In addition, integration of this accelerated solver into control systems could enable adaptive real-time decision making during RF heating experiments, in a manner similar to the approach in machine learning-based real-time kinetic profile reconstruction for real-time reconstruction of the kinetic profile between pedestal regions. The natural next step will explore multiphysics coupling, higher-fidelity data generation on heterogeneous computing platforms, and scaling the approach to other geometry and reactor-grade devices such as ITER (International Thermonuclear Experimental Reactor) or DEMO (DEMOnstration Power Plant), solidifying the role of physics-based machine learning in next-generation fusion research.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to express his deepest gratitude to Dr. Naoto Tsujii from the University of Tokyo for his generous remote guidance on the theoretical foundation of this work and for providing valuable parameters and fruitful discussions related to the TST-2 spherical tokamak. Sincere thanks are also extended to Dr. Adriana Paluszny for her guidance on scientific writing and supervision on the overall project timeline through weekly stand-up meetings. The author acknowledges Mr. Rayan Khan from the Imperial College Remote Computing Service (RCS) for granting PBS job priority access, and Dr. Marijan Beg and Mr. Francois Schalkwyk from the Department of Earth Science and Engineering – BORG Computing Team for their timely support of departmental A100 GPU resources during periods of high demand on RCS’s GPU resources.

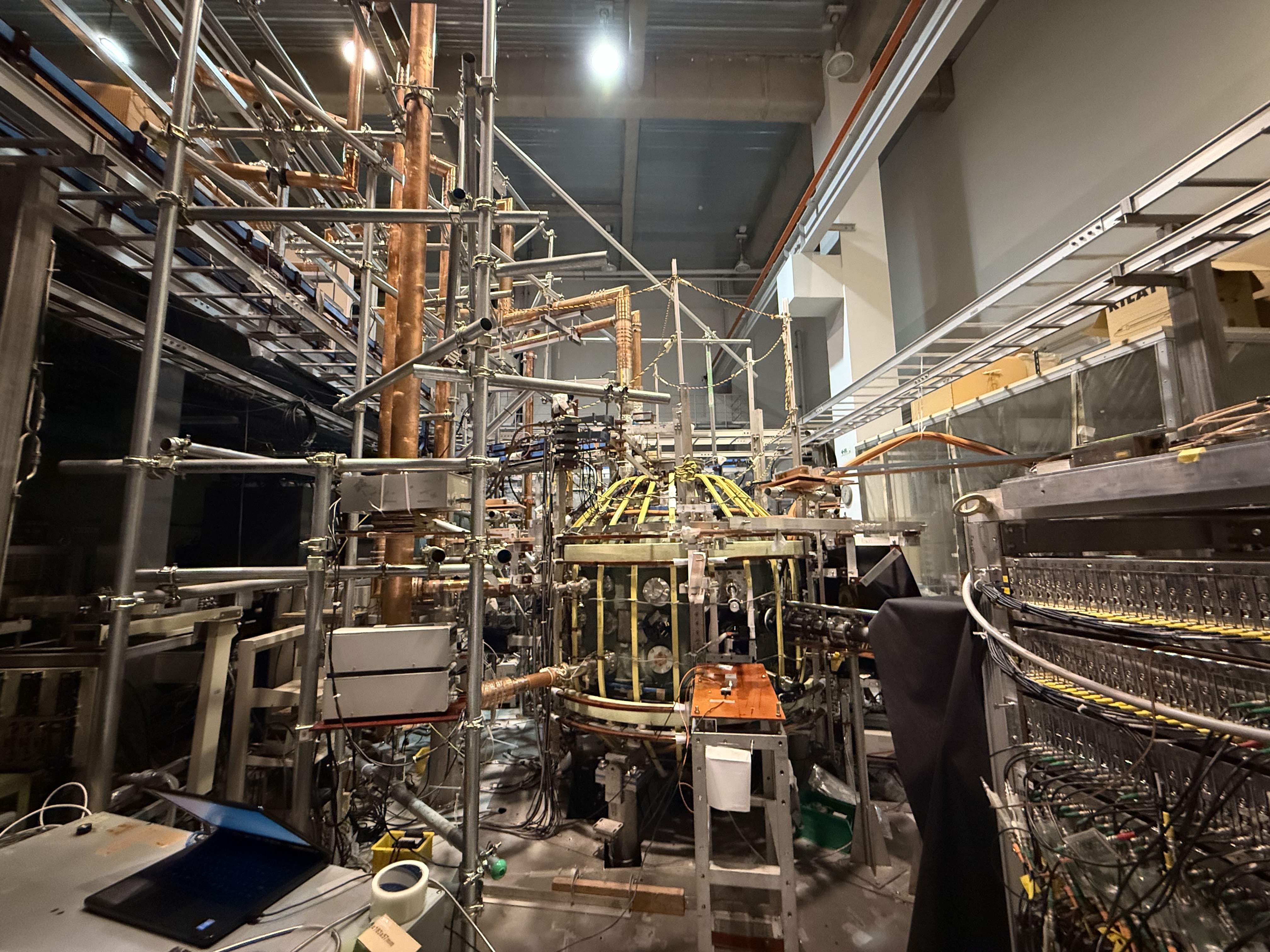

Special thanks to Mr. Koshi Yoshida, Mr. Suebsak Suksaengpanomrung and Mr. Tang Zhexuan from the Ejili–Tsujii Laboratory at the University of Tokyo for their warm introduction to the TST-2 operations during the author’s visit and to Mr. En-Rui Chang from Liscotech System Co., Ltd. for valuable discussions on antenna design and operation.

References

- Jaeger, E. F. et al. (2001) ‘All-orders spectral calculation of radio-frequency heating in two-dimensional toroidal plasmas’, Physics of Plasmas, 8(5), pp. 1573–1583. doi: 10.1063/1.1359516

- Adachi, F. et al. (2024) ‘Two-Dimensional Axisymmetric Finite Element Simulation of Lower Hybrid Wave with an Iterative Scheme’, Plasma and Fusion Research, 19, p. 1403026. doi: 10.1585/pfr.19.1403026

- Ko, Y. et al. (2023) ‘Development of an outer-off-midplane lower hybrid wave launcher for improved core absorption in non-inductive plasma start-up on TST-2’, Nuclear Fusion, 63(12), p. 126015. doi: 10.1088/1741-4326/acf5ff

- Fisch, N. J. (1978) ‘Confining a Tokamak Plasma with rf-Driven Currents’, Phys. Rev. Lett., 41(13), pp. 873–876. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.41.873

- Kaltsas, D. A. et al. (2024) ‘Axisymmetric hybrid Vlasov equilibria with applications to tokamak plasmas’, Plasma Physics and Controlled Fusion, 66(6), p. 065016. doi: 10.1088/1361-6587/ad4174

- Raissi, M. et al. (2019) ‘Physics-informed neural networks: A deep learning framework for solving forward and inverse problems involving nonlinear partial differential equations’, Journal of Computational Physics, 378, pp. 686–707. doi: 10.1016/j.jcp.2018.10.045

- Eivazi, H. et al. (2022) ‘Physics-informed neural networks for solving Reynolds-averaged Navier–Stokes equations’, Physics of Fluids, 34(7), p. 075117. doi: 10.1063/5.0095270

- Rasht-Behesht, M. et al. (2022) ‘Physics-Informed Neural Networks (PINNs) for Wave Propagation and Full Waveform Inversions’, Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth, 127(5), p. e2021JB023120. doi: 10.1029/2021JB023120

- Lucor, D. et al. (2022) ‘Simple computational strategies for more effective physics-informed neural networks modeling of turbulent natural convection’, Journal of Computational Physics, 456, p. 111022. doi: 10.1016/j.jcp.2022.111022

- Li, Z. et al. (2021) ‘Fourier Neural Operator for Parametric Partial Differential Equations’, International Conference on Learning Representative (ICLR). doi: 10.48550/arXiv.2010.08895

- Li, Z. et al. (2023) ‘Fourier Neural Operator with Learned Deformations for PDEs on General Geometries’, Journal of Machine Learning Research, 24, pp. 1–26.

- Li, Z. et al. (2024) ‘Physics-Informed Neural Operator for Learning Partial Differential Equations’, ACM / IMS Journal of Data Science, 1(3), pp. 1–27. doi: 10.1145/3648506

- Ronneberger, O. et al. (2015) ‘U-Net: Convolutional Networks for Biomedical Image Segmentation’. arXiv:1505.04597. doi: 10.48550/arXiv.1505.04597

- Wesson, J. (2011) Tokamaks, 4th edn., Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

- Swanson, D. G. (2003) Plasma Waves, 2nd edn., Boca Raton: CRC Press.

- Stix, T. H. (1992) Waves in Plasmas, New York: American Institute of Physics.

- Antony, A. N. M. et al. (2023) ‘FDM data driven U-Net as a 2D Laplace PINN solver’, Scientific Reports, 13, 9116. doi: 10.1038/s41598-023-35531-8

- Zhang, Z. (2022) ‘A physics-informed deep convolutional neural network for simulating and predicting transient Darcy flows in heterogeneous reservoirs without labeled data’, Journal of Petroleum Science and Engineering, 211, p. 110179. doi: 10.1016/j.petrol.2022.110179

- Lecun, Y. et al. (1998) ‘Gradient-based learning applied to document recognition’, Proceedings of the IEEE, 86(11), pp. 2278–2324. doi: 10.1109/5.726791

- Li, C. (2023) ‘Assessing the Performance of PINN and CNN Approaches in Solving the 1D Burgers’ Equation with Deep Learning Architectures’, 2023 4th International Conference on Machine Learning and Computer Application. doi: 10.1145/3650215.3650370

- Krizhevsky, A. et al. (2012) ‘ImageNet Classification with Deep Convolutional Neural Networks’, Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 25 (NeurIPS 2012).

- Gopakumar, V. et al. (2024) ‘Plasma surrogate modelling using Fourier neural operators’, Nuclear Fusion, 64, p. 056025. doi: 10.1088/1741-4326/ad313a

- Sitzmann, V. et al. (2020) ‘Implicit Neural Representations with Periodic Activation Functions’, 34th Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS 2020). doi: 10.48550/arXiv.2006.09661

- McGreivy, N. and Hakim, A. (2024) ‘Weak baselines and reporting biases lead to overoptimism in machine learning for fluid-related partial differential equations’, Nature Machine Intelligence, 6, pp. 1256–1269. doi: 10.1038/s42256-024-00897-5

- Shousha, R. et al. (2023) ‘Machine learning-based real-time kinetic profile reconstruction in DIII-D’, Nuclear Fusion, 64, p. 026006. doi: 10.1088/1741-4326/ad142f

- Wang, Z. et al. (2004) ‘Image quality assessment: from error visibility to structural similarity’, IEEE Transactions on Image Processing, 13(4), pp. 600-612. doi: 10.1109/TIP.2003.819861