Numerical Methods and Physics Informed Neural Networks in Advection Function

Kozak Hou

Problem Statement

The advection equation is a simple partial differential equation that describes the transport of a quantity by a velocity field. It is a fundamental equation in fluid dynamics and is used to model a wide range of physical phenomena. The advection equation is given by:

\[\frac{\partial u}{\partial t} + c \frac{\partial u}{\partial x} = 0\]or in vector form:

\[\frac{\partial u}{\partial t} + \nabla \cdot (u \mathbf{v}) = 0\]where \(u\) is the quantity being transported, \(\mathbf{v}\) is the velocity field, and \(\nabla \cdot\) is the divergence operator. The advection equation is a hyperbolic partial differential equation and is known to exhibit sharp gradients and discontinuities in the solution. This makes it challenging to solve numerically, especially when the velocity field is complex or discontinuous.

Numerical Methods

There are several numerical methods that can be used to solve the advection equation. Some of the most common methods include finite difference methods, finite volume methods, and finite element methods. These methods discretize the advection equation in space and time and solve the resulting system of algebraic equations to obtain an approximate solution. However, these methods can be computationally expensive and may not be accurate for problems with sharp gradients or discontinuities.

Finite Difference Methods (FDM)

Finite difference methods discretize the advection equation in space and time using a grid of points. The equation is approximated at each grid point using a finite difference approximation, and the resulting system of algebraic equations is solved using an iterative method. Finite difference methods are simple to implement and are computationally efficient for problems with smooth solutions. However, they can be inaccurate for problems with sharp gradients or discontinuities.

How to obtain the discrete form from differential equation via FDM ?

Forward Difference Approximation

The forward difference approximation is a simple method for approximating the derivative of a function at a point. It is based on the definition of the derivative as the limit of the difference quotient as the step size approaches zero. The forward difference approximation is given by:

\[f'(x) \approx \frac{f(x + h) - f(x)}{h}\]where \(f'(x)\) is the derivative of the function \(f\) at the point \(x\), \(h\) is the step size, and \(f(x + h)\) is the value of the function at the point \(x + h\).

Backward Difference Approximation

The backward difference approximation is another simple method for approximating the derivative of a function at a point. It is based on the definition of the derivative as the limit of the difference quotient as the step size approaches zero. The backward difference approximation is given by:

\[f'(x) \approx \frac{f(x) - f(x - h)}{h}\]where \(f'(x)\) is the derivative of the function \(f\) at the point \(x\), \(h\) is the step size, and \(f(x - h)\) is the value of the function at the point \(x - h\).

Central Difference Approximation

The central difference approximation is a more accurate method for approximating the derivative of a function at a point. It is based on the definition of the derivative as the limit of the difference quotient as the step size approaches zero. The central difference approximation is given by:

\[f'(x) \approx \frac{f(x + h) - f(x - h)}{2h}\]where \(f'(x)\) is the derivative of the function \(f\) at the point \(x\), \(h\) is the step size, and \(f(x + h)\) and \(f(x - h)\) are the values of the function at the points \(x + h\) and \(x - h\), respectively.

Discrete Form of the Advection Equation

To acquire the discrete form of the advection equation, we can use the forward difference approximation for the time derivative and the backward difference approximation for the spatial derivative. The discrete form of the advection equation is given by:

We can use the forward difference approximation for the time derivative and the backward difference approximation for the spatial derivative to obtain the discrete form of the advection equation.

Forward Difference Approximation for Time Derivative

\(\frac{\partial u}{\partial t} \approx \frac{u_{i}^{n+1} - u_{i}^{n}}{\Delta t}\)

where \(u_{i}^{n}\) is the value of \(u\) at grid point \(i\) and time step \(n\), \(u_{i}^{n+1}\) is the value of \(u\) at grid point \(i\) and time step \(n+1\), and \(\Delta t\) is the time step size.

Backward Difference Approximation for Spatial Derivative

\(\frac{\partial u}{\partial x} \approx \frac{u_{i}^{n} - u_{i-1}^{n}}{\Delta x}\)

where \(u_{i}^{n}\) is the value of \(u\) at grid point \(i\) and time step \(n\), \(u_{i-1}^{n}\) is the value of \(u\) at grid point \(i-1\) and time step \(n\), and \(\Delta x\) is the spatial step size.

Then we can substitute these approximations into the advection equation to obtain the discrete form:

\[\frac{u_i^{n+1} - u_i^n}{\Delta t} + c \frac{u_i^n - u_{i-1}^n}{\Delta x} = 0\]where \(u_i^{n+1}\) is the value of \(u\) at grid point \(i\) and time step \(n+1\), \(u_i^n\) is the value of \(u\) at grid point \(i\) and time step \(n\), \(u_{i-1}^n\) is the value of \(u\) at grid point \(i-1\) and time step \(n\), \(\Delta t\) is the time step size, \(\Delta x\) is the spatial step size, and \(c\) is the advection velocity.

CFL Condition

The Courant-Friedrichs-Lewy (CFL) condition is a stability criterion that must be satisfied for finite difference methods to produce accurate results. The CFL condition is given by:

\[\text{CFL} = \frac{c \Delta t}{\Delta x} \leq 1\]where \(c\) is the advection velocity, \(\Delta t\) is the time step size, and \(\Delta x\) is the spatial step size. The CFL condition ensures that information propagates through the grid at a rate that is consistent with the advection velocity. If the CFL condition is not satisfied, the finite difference method may produce inaccurate results or become unstable.

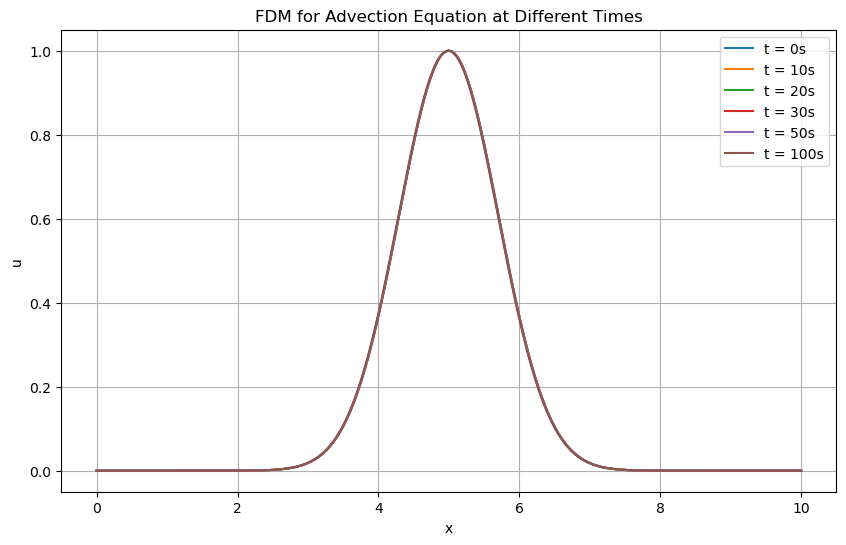

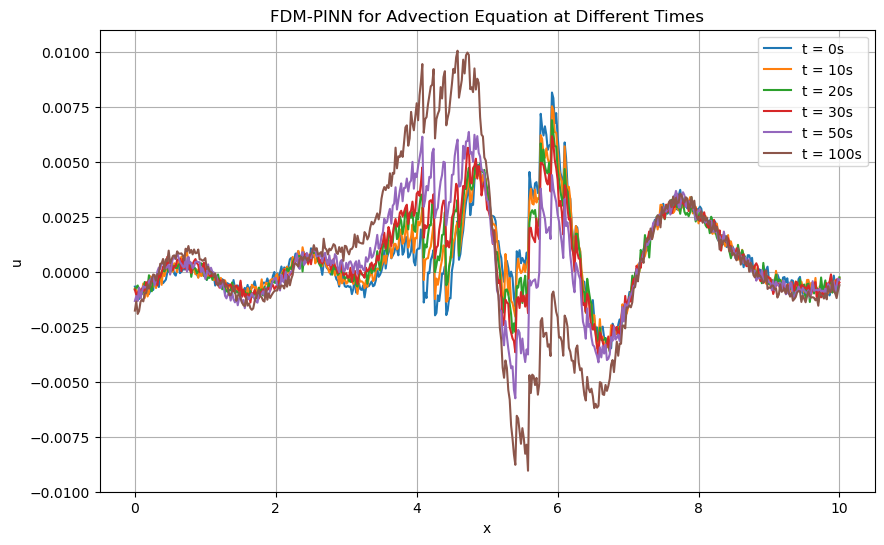

FDM for Advection Equation (I.C.: Gaussian Pulse, Periodic B.C., c=0.0001)

Finite Volume Methods (FVM)

Finite volume methods discretize the advection equation in space using a grid of control volumes. The equation is integrated over each control volume, and the resulting system of algebraic equations is solved to obtain an approximate solution. Finite volume methods are conservative and can accurately capture sharp gradients and discontinuities in the solution. However, they can be computationally expensive and may require a large number of grid points to obtain an accurate solution.

To acquire the discrete form of the advection equation, we can integrate the equation over a control volume and apply the divergence theorem.

Control Volume

A control volume is a region of space over which the advection equation is integrated. The control volume is defined by a set of boundaries, and the advection equation is integrated over the volume enclosed by these boundaries. The control volume is typically chosen to be a regular shape, such as a cube or a cylinder, to simplify the integration process.

Apply integration over both the spatial domain \(V\) (control volume between \(x_{i-1/2}\) and \(x_{i+1/2}\)) and time (from \(t_n\) to \(t_{n+1}\)):

which means that:

\[\int_{V} \frac{\partial u}{\partial t} dV + \int_{V} \nabla \cdot (u \mathbf{v}) dV = 0\]is equal to

\[\int_{t_n}^{t_{n+1}} \int_{x_{i-1/2}}^{x_{i+1/2}} \frac{\partial u}{\partial t} dx dt + \int_{t_n}^{t_{n+1}} \int_{x_{i-1/2}}^{x_{i+1/2}} \nabla \cdot (u \mathbf{v}) dx dt = 0\]Then for the temporal term, we use:

\[\left[ \int_{x_{i-1/2}}^{x_{i+1/2}} u \, dx \right]_{t_n}^{t_{n+1}}\]and for the spatial term (assume \(\mathbf{n}\) is constant over the control volume boundary):

\[\int_{t_n}^{t_{n+1}} \left( u v \right)_{x_{i+1/2}} \, dt - \int_{t_n}^{t_{n+1}} \left( u v \right)_{x_{i-1/2}} \, dt\]where \(\mathbf{n}\) is the outward unit normal vector to the control volume boundary.

Discretization

Assume \(u\) is approximated at the surfaces \(x_{i+1/2}\) and \(x_{i-1/2}\) using suitable interpolation schemes and that \(u\) remains constant over small time intervals:

\[\Delta x \left(u_i^{n+1} - u_i^n\right) + \Delta t \left[ (u v)_{i+1/2}^{n} - (u v)_{i-1/2}^{n} \right] = 0\]Then we can rearrange the terms to obtain the discrete form of the advection equation:

\[u_i^{n+1} = u_i^n - \frac{\Delta t}{\Delta x} \left[ (u v)_{i+1/2}^{n} - (u v)_{i-1/2}^{n} \right]\]

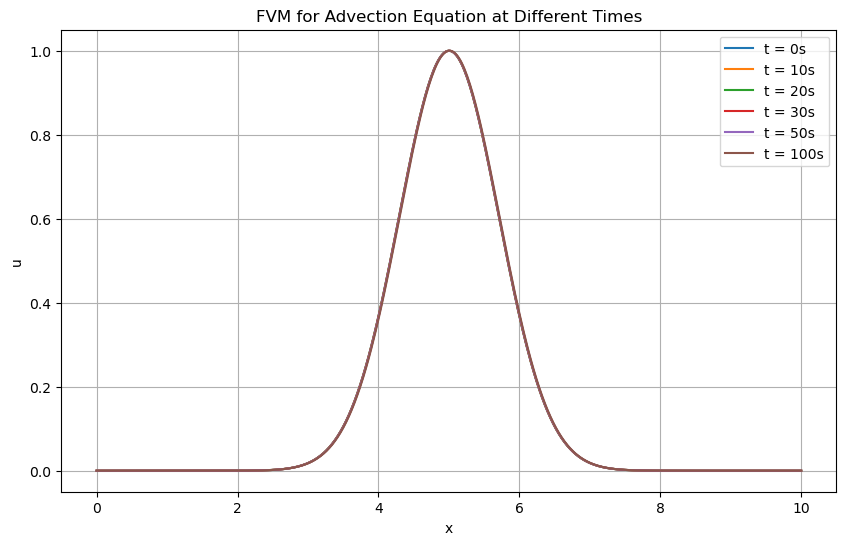

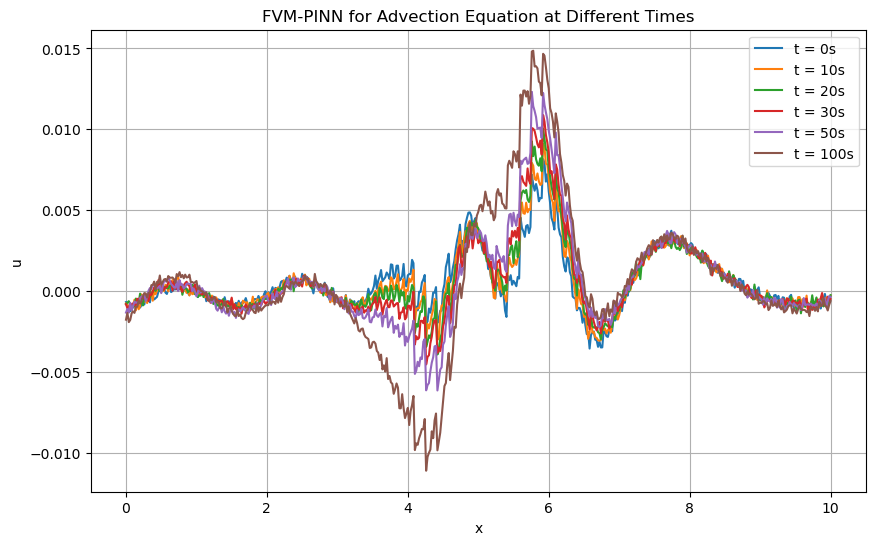

FVM for Advection Equation (I.C.: Gaussian Pulse, Periodic B.C., c=0.0001)

Reminder

This project is dedicated on researching in the FDM, FVM and PINN, whereas Finite Element Method (FEM) won’t be discussed in this project. If you are interested in the Finite Element Method, you can refer to the following section.

Finite Element Methods (FEM)

Finite element methods discretize the advection equation in space using a mesh of elements. The equation is approximated over each element using a set of basis functions, and the resulting system of algebraic equations is solved to obtain an approximate solution. Finite element methods are flexible and can handle complex geometries and boundary conditions. However, they can be computationally expensive and may require a large number of elements to obtain an accurate solution.

To acquire the discrete form of the advection equation, we can use the Galerkin method to approximate the solution over each element.

Finite Element Mesh

Apply the Galerkin method to approximate the solution over each element:

\[\int_{\Omega} \frac{\partial u}{\partial t} \phi_i d\Omega + \int_{\Omega} \nabla \cdot (u \mathbf{v}) \phi_i d\Omega = 0\]where \(\phi_i\) is the basis function associated with node \(i\) and \(\Omega\) is the spatial domain of the advection equation.

Then we can use the divergence theorem to convert the second term into a surface integral:

\[\int_{\Omega} \frac{\partial u}{\partial t} \phi_i d\Omega + \int_{\partial \Omega} (u \mathbf{v} \cdot \mathbf{n}) \phi_i dS = 0\]where \(\partial \Omega\) is the boundary of the spatial domain and \(\mathbf{n}\) is the outward unit normal vector to the boundary.

Then we can apply the Galerkin method to approximate the solution over each element:

\[\int_{\Omega_e} \frac{\partial u}{\partial t} \phi_i d\Omega + \int_{\partial \Omega_e} (u \mathbf{v} \cdot \mathbf{n}) \phi_i dS = 0\]where \(\Omega_e\) is the element domain and \(\partial \Omega_e\) is the boundary of the element.

Then we can use the basis functions to approximate the solution over each element:

\[u_h = \sum_{i=1}^{N} u_i \phi_i\]where \(u_h\) is the approximate solution, \(u_i\) is the value of the solution at node \(i\), and \(\phi_i\) is the basis function associated with node \(i\).

Then we can substitute the approximate solution into the Galerkin method to obtain the discrete form of the advection equation:

\[\int_{\Omega_e} \frac{\partial u_h}{\partial t} \phi_i d\Omega + \int_{\partial \Omega_e} (u_h \mathbf{v} \cdot \mathbf{n}) \phi_i dS = 0\]where \(u_h\) is the approximate solution, \(\phi_i\) is the basis function associated with node \(i\), and \(\Omega_e\) is the element domain.

In this project, we won’t make further discussion on FEM, but we will focus on the comparison of FDM, FVM, and PINNs.

Physics Informed Neural Networks (PINNs)

Physics Informed Neural Networks (PINNs) are a class of neural networks that are trained to approximate the solution of a partial differential equation (PDE) while satisfying the boundary and initial conditions of the problem. PINNs combine the flexibility of neural networks with the physical constraints of the PDE to obtain an accurate and efficient solution. PINNs have been successfully applied to a wide range of problems in fluid dynamics, heat transfer, and structural mechanics.

To acquire the discrete form of the advection equation using PINNs, we can use the neural network to approximate the solution and the PDE loss to enforce the physical constraints.

Neural Network Architecture

The neural network architecture for PINNs typically consists of two parts: a physics-informed part that approximates the solution of the PDE and a data-driven part that approximates the boundary and initial conditions. The physics-informed part is trained to minimize the PDE loss, while the data-driven part is trained to minimize the boundary and initial condition loss.

PDE Loss

The PDE loss is used to enforce the physical constraints of the advection equation. It is defined as the residual of the PDE at a set of collocation points:

\[\mathcal{L}_{\text{PDE}} = \sum_{i=1}^{N_{\text{PDE}}} \left| \frac{\partial u}{\partial t} + \nabla \cdot (u \mathbf{v}) \right|^2\]where \(N_{\text{PDE}}\) is the number of collocation points and \(u\) is the approximate solution of the advection equation.

Boundary and Initial Condition Loss

The boundary and initial condition loss is used to enforce the boundary and initial conditions of the advection equation. It is defined as the difference between the approximate solution and the true solution at a set of boundary and initial points:

\[\mathcal{L}_{\text{BC}} = \sum_{i=1}^{N_{\text{BC}}} \left| u - u_{\text{true}} \right|^2\]where \(N_{\text{BC}}\) is the number of boundary and initial points, \(u\) is the approximate solution of the advection equation, and \(u_{\text{true}}\) is the true solution of the advection equation.

Total Loss

The total loss is the sum of the PDE loss and the boundary and initial condition loss:

\[\mathcal{L}_{\text{total}} = \mathcal{L}_{\text{PDE}} + \mathcal{L}_{\text{BC}}\]The neural network is trained to minimize the total loss using gradient-based optimization methods such as stochastic gradient descent or Adam.

Comparison of Numerical Methods and PINNs

Let’s Recap the advective equation:

\[\frac{\partial u}{\partial t} + c \frac{\partial u}{\partial x} = 0\]where \(u\) is the quantity being transported and \(c\) is the advection velocity.

Initial Conditions and Boundary Condition

Define computational domain and mesh resolution, initial conditions, and boundary conditions.

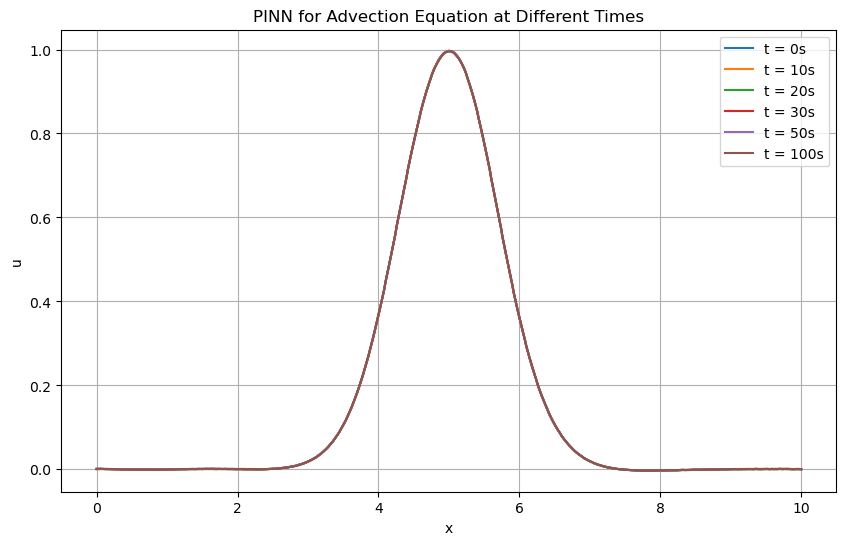

1D domain \(x \in [0, L]\) with periodic boundary conditions with advection velocity \(c = 0.0001\), \(L = 10\), \(n\) = \(501\) and \(dt\) = 0.01.

Initial condition: \(u(x, 0) = e^{-(x-(L/2)**2)/(0.1*10)}\)

Comparison of numerical methods and PINNs for solving the advection equation.

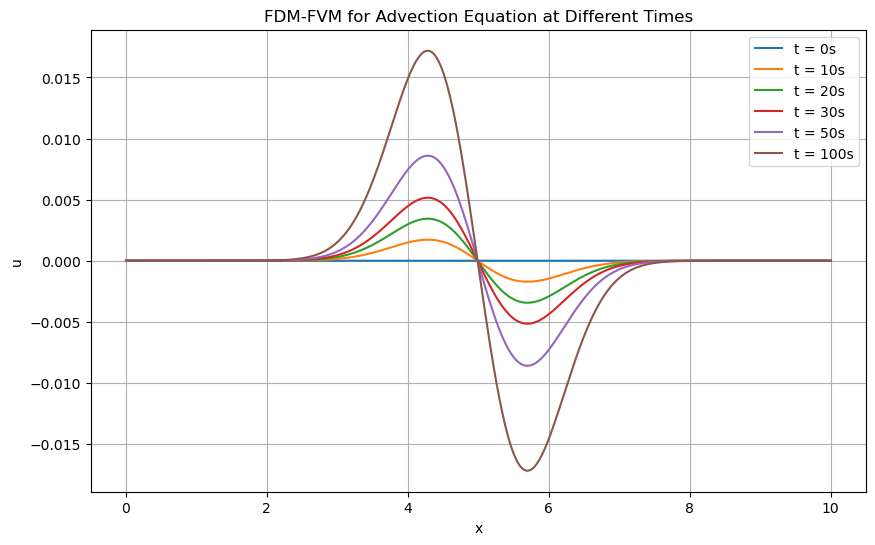

Residual plot of the PINNs between FDM and FVM for solving the advection equation.

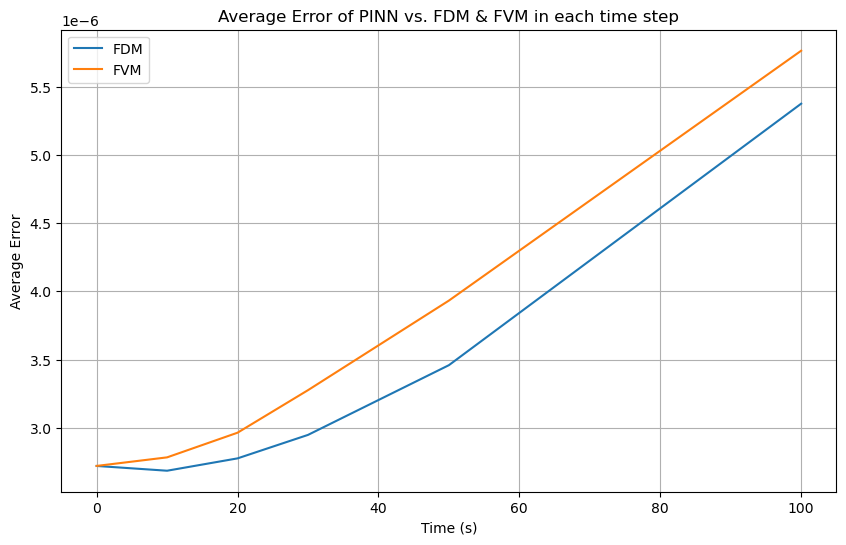

Average error of PINN vs. FDM & FVM in each time step

Conclusion

From the residual plot and average error plot, we can see that the PINNs are able to approximate the solution of the advection equation with high accuracy and efficiency in a \(10^{-6}\) order of magnitude. We can also observe that the PINNs have a slightly oscillatory behavior in the residual plot, which is due to the neural network’s approximation of the solution, whereas the FDM and FVM have a more stable behavior. This can be seen as evidence that the PINNs are able to capture the solution of the advection equation with high accuracy but may require more computational resources to achieve the same level of accuracy as the FDM and FVM. Nevertheless, this issue is too simple to be considered a major drawback of the PINNs, and PINNs can be a powerful tool for solving complex problems in fluid dynamics and other fields which generally require high computational resources. With the advantage of high efficiency in inferring the solution with inarguable accuracy, PINNs can be a better choice.

References

-

Chakraverty, S., Mahato, N., Karunakar, P., & Rao, T. D. (2019). Advanced numerical and semi-analytical methods for differential equations. Wiley.

-

Bhaskaran, R., & Collins, L. (2012). Introduction to CFD basics. Retrieved from https://dragonfly.tam.cornell.edu/teaching/mae5230-cfd-intro-notes.pdf.